Introduction to Swift Metatypes

Metatypes can be difficult to grasp, both in concept and application. My hope is that after reading this, you’ll have mastered the basics of metatypes!

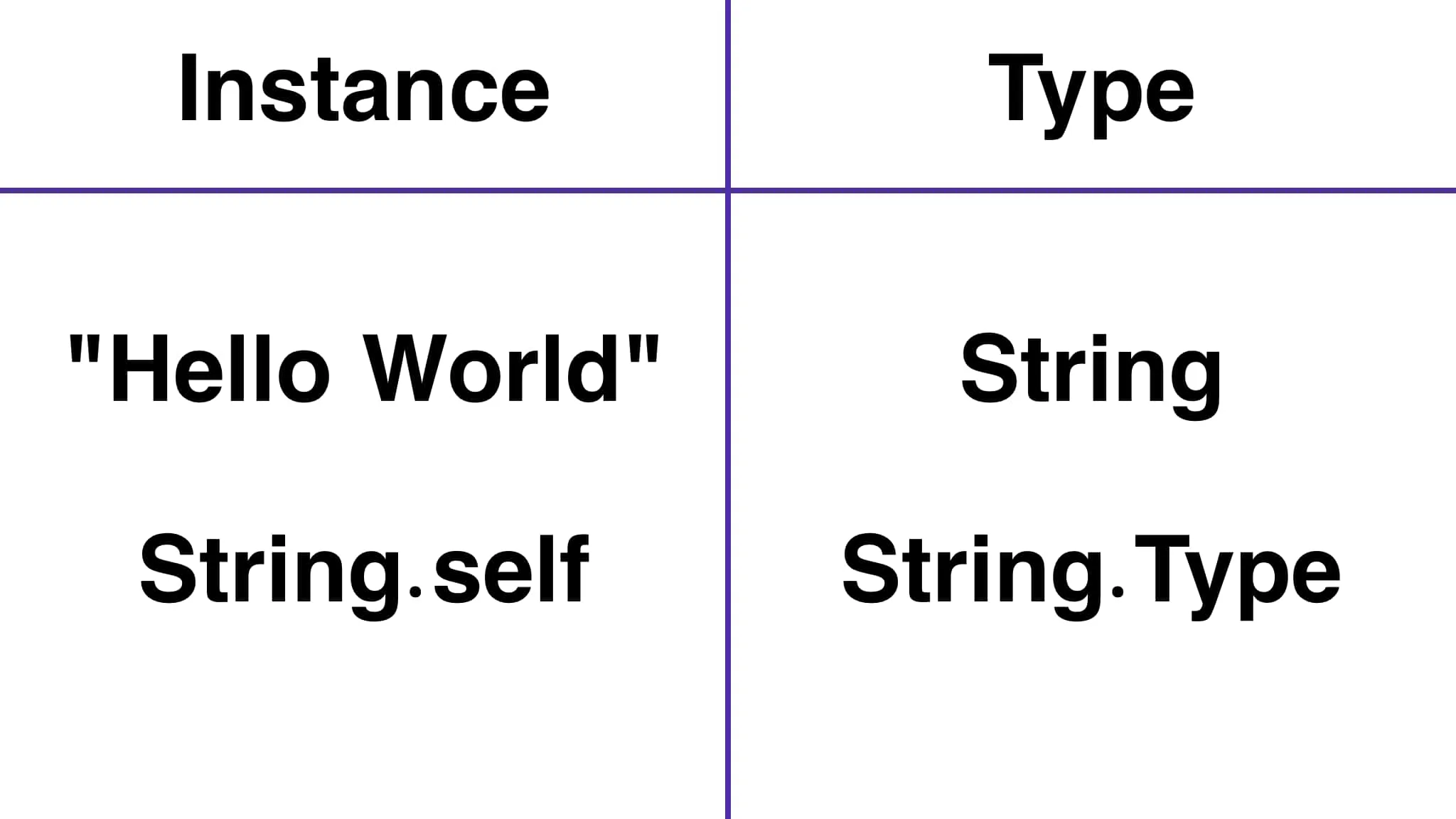

Instances & Types

To understand metatypes, it helps to start with the familiar. For example, just as String is the type of "Hello World", String.Type is the type of String.self. While String is the type of an instance, String.Type is the type of a type—hence the name “metatype”.

Here is an illustration in code:

let myString: String = "Hello World!"

let myStringType: String.Type = String.selfAnd since a metatype is a type, we can specify it as such in function signatures:

func doSomething(with type: String.T

ype) { ... } // Specify a metatype parameter

doSomething(with: String.self) // Pass in a metatype instanceThis works if you know what metatype instance you want to pass in at compile time. But what if you have an object and need to get its metatype at runtime? Never fear! Simply use the type(of:) method, like so:

let myString = "Hello, world!"

let myStringType = type(of: myString) // converts an instance to its metatype value.

doSomething(with: myStringType)This seems pointless with String, but if you have a class with many subclasses, you wouldn’t know which subclass-type you’re dealing with. Passing the object to type(of:) allows you to get the metatype instance.

Now that we know how to create instances of a metatype, let’s briefly discuss what we’re able to do with them.

Application

Metatypes are used to access properties and methods that belong to the type. This includes anything marked as static, class, and init.

class SomeClass {

static let someKey = "0000"

init() { ... }

static func someMethod() { ... }

}

let key = SomeClass.someKey // Shorthand for SomeClass.self.someKey

let someClass = SomeClass() // Shorthand for SomeClass.self.init()

SomeClass.someMethod() // Shorthand for, you guessed it, SomeClass.self.someMethod()While we don’t see a metatype instance, we are actually using metatypes to perform all these actions! For instance, SomeClass.someKey is the same as SomeClass.self.someKey, but Swift hides all the clutter from us. I typically add properties and methods to types when there’s a piece of functionality that isn’t dependent on an instance.

Fun fact, this is exactly what is being done when you pass a metatype to a JSONDecoder’s decode method:

// JSONDecoder's method

func decode<T>(T.Type, from: Data) -> T { ... }

let decoder = JSONDecoder()

decoder.decode(SomeClass.self, from: someData) // now JSON Decoder has access to SomeClass' init method.Conclusion

To summarize:

- A metatype is simply a type with

.Typeappended to it, e.g.String.Type - A metatype instance can be specified by appending

.selfto a type, e.g.String.self - To get a metatype instance at runtime, simply pass an instance to

type(of:) - Metatypes allow access to properties, methods, and initializers belonging to the type.

I hope you found this explanation of metatypes useful! We have only scratched the surface, however. For a deeper dive with more examples, please see Bruno Rocha’s excellent post on Metatypes!